Equines are extremely large prey animals that can weigh about 2,200 pounds. This large quantity of body weight requires anatomical mechanisms to provide stability for limbs without exacerbating their muscles. The pelvic limb carries about forty percent of a horse’s weight by utilizing their patellar locking mechanism, reciprocal apparatus, and suspensory apparatus. However, the thoracic limb is responsible for carrying sixty percent of the horse’s weight and uses similar mechanisms to support this limb. The thoracic limb is supported by muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

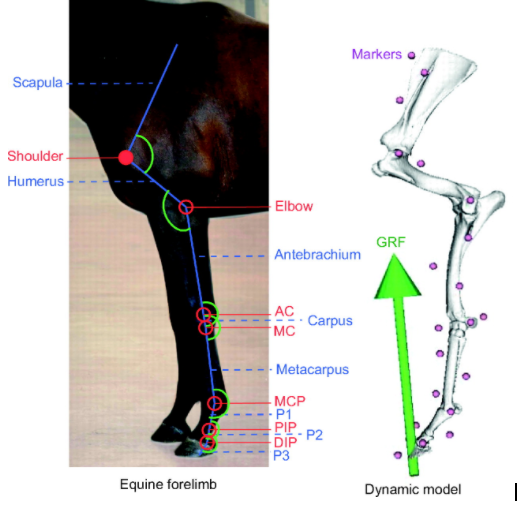

The most cranial aspect of the forelimb that provides the majority of the weight bearing support is the serratus ventralis muscle. Serratus ventralis is an extrinsic muscle, meaning it attaches the limb to the rest of the body. It specifically originates on the thoracic trunk and inserts on the dorsum of the scapula bone. This is extremely important because there is not a joint that connects the scapula to the thoracic trunk, but rather, nine extrinsic muscles that hold the limb in place. The first actual joint that is involved with the stabilization of the forelimb is the scapulohumeral joint.

The scapulohumeral joint is a multiaxial joint that allows the limb to extend, flex, abduct, and adduct in order to rotate the limb. Intrinsic muscles, specifically biceps brachii, give support to this joint and prevent the limb from collapsing into a flexion state while standing. Further, biceps brachii has a central tendon in the middle of the muscle belly that presses against the cranial surface of the shoulder creating a cap over the intermediate tubercle of the intermediate tubercle groove that enables the joint to lock. Due to these strong muscles and tendons this joint only requires weak collateral ligaments to add a little more support. However, the radioulnar humeral joint requires strong collateral ligaments to allow the horse to maintain the extension of the elbow in a standing position.

The radioulnar joint is a composite joint composed of three synovial joints: humerus-ulna joint, humerus-radial joint, and proximal radius-ulna joint. These are hinge joints that allow extension and flexion of the elbow. In smaller mammals, the proximal radioulnar joint allows pronation and supination to occur, but in larger animals this range of movement is immobile. The major muscle that maintains tone is the triceps brachii muscle. This is important because it protects the limb from falling into a state of flexion. This mechanism is supported by strong collateral ligaments that help maintain the preferred state of extension. Moving down the limb, the carpal joint is supported in a similar manner.

The carpal joints ensure the carpus in a naturally extended state and is composed of the antebrachial carpal joint, midcarpal joint, and carpometacarpal joint. The movement decreases as you move down the limb in each of these joints because the antebrachial carpal joint is a synovial joint, the middle carpal joint is a hinge joint, and the carpometacarpal joint has no movement. One of the muscles that supports this muscle is biceps brachii which attaches to the lacertus fibrosis, a ligamentous tissue, in order to stabilize these joints. The other important muscle that stabilizes these joints is the extensor carpi radialis muscle. These extensor muscles are then protected and held in place by extensor retinaculum, which is deep fascia, on the dorsal side of the limb. Similarly, the Flexor muscles are held in place flexor retinaculum.

As we move toward the palmar aspect of the limb, the fetlock joint is stabilized by muscles that extend into tendons as well as supporting ligaments. There are two tendons that run caudally down the limb that originate from the superficial digital flexor muscle and deep digital flexor muscle. The superficial digital flexor has a ligamentous branch, the proximal check ligament, that helps support the proximal interphalangeal joints of the fetlock. The tendon of deep digital flexor muscle also has a ligamentous branch, the distal check ligament, that supports the carpus, proximal and distal interphalangeal joint. This is especially important because it is the only support for the distal interphalangeal joint. Also, there is the suspensory apparatus composed of the interosseous muscle, and proximal/ distal sesamoidean ligaments that help support the fetlock.

These highly specific anatomical features allow this massive animal to stabilize the thoracic limb. It is astonishing how complex these structures are and how the work simultaneously together to allow this animal to stand for extended periods of time by keeping the limb in extension and run up to fifty miles an hour. Equine anatomy is very unique which is suiting because a 2000 pound pray animal is very unique.